Why Socializing After Injury Feels So Hard — And What No One Tells You

Recovering from an injury isn’t just about physical healing — it’s also emotional and social. I used to think going out with friends would lift my mood during rehab, but instead, I felt drained, anxious, and out of place. Turns out, jumping back into social life too soon can actually slow recovery. This article explores the hidden pitfalls of social activities in rehabilitation, why well-meaning outings can backfire, and how to reconnect safely without sacrificing progress. The journey to healing involves more than movement and medicine; it requires understanding how our minds and relationships respond to change, limitation, and the quiet process of rebuilding.

The Pressure to “Get Back to Normal”

After an injury, many individuals face an unspoken expectation: return to life as it was. Family members may say, “You’ll be back on your feet in no time,” while friends invite you to gatherings with cheerful confidence. These messages, though well-intentioned, can create emotional strain. The desire to appear strong or not disappoint loved ones often leads people to accept invitations they’re not ready for. The truth is, recovery doesn’t follow a calendar or social schedule. Physical healing timelines vary, and emotional readiness lags even further behind.

Returning to normal activities too soon isn’t a sign of strength — it’s a risk. The human body needs time to repair tissues, rebuild strength, and retrain movement patterns. Equally important, the mind needs space to adjust to new limitations and uncertainties. When someone attends a party or dinner shortly after surgery or trauma, they may appear fine on the surface, but internally, their system is working overtime to manage pain, fatigue, and sensory input. This mismatch between outward appearance and internal reality can deepen feelings of isolation.

The pressure to “get back to normal” often comes from a cultural narrative that values productivity and visibility. We’re taught that pushing through difficulty is admirable, but in rehabilitation, pacing is more powerful than persistence. Choosing to stay home is not failure — it’s an act of wisdom. Validating the hesitation to re-engage socially allows space for honest healing. Accepting that recovery includes phases of withdrawal and recalibration helps reduce guilt and supports long-term progress.

When Socializing Drains Instead of Energizes

Most people assume social interaction is naturally energizing. Laughter, conversation, and shared moments are often linked to improved mood. However, for someone in recovery, these same experiences can feel exhausting rather than uplifting. This shift happens because the brain and body are already using significant resources to manage pain, inflammation, and tissue repair. Adding social demands — interpreting facial expressions, following fast-paced dialogue, filtering background noise — increases cognitive load in ways that aren’t immediately obvious.

Fatigue after injury is not the same as ordinary tiredness. It’s a deep, systemic exhaustion that stems from the nervous system being in a prolonged state of alert. Even mild pain signals require constant attention from the brain, leaving less capacity for social processing. In environments like crowded restaurants or lively gatherings, multiple stimuli — lights, sounds, movement — can overwhelm the senses. This sensory sensitivity is especially common after neurological injuries, orthopedic surgeries, or chronic conditions, but it can affect anyone healing from physical trauma.

Imagine sitting at a dinner table with five friends. The conversation flows quickly, someone tells a joke, and laughter erupts. To a healthy person, this feels joyful. To someone in recovery, it may feel disorienting. Keeping up with the dialogue requires mental effort. The clatter of dishes, the hum of music, and the shifting light from candles all add to the burden. By the end of the evening, the person may feel emotionally flat or even irritable — not because they dislike their friends, but because their nervous system reached its limit.

Recognizing that socializing can be draining is a crucial step in protecting recovery. It shifts the focus from “why don’t I feel happy?” to “what is my body telling me?” This awareness allows individuals to plan interactions more thoughtfully, choosing shorter, quieter events that align with their current capacity. Energy is a finite resource during healing, and how it’s spent matters deeply.

Misunderstanding and Invisible Barriers

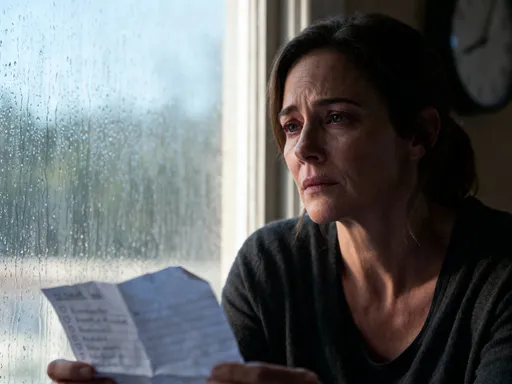

One of the most painful aspects of recovery is the gap between how someone feels and how they appear. To the outside world, a person may look fine — walking without assistance, smiling during conversation, dressed normally. But beneath the surface, they may be managing chronic pain, brain fog, or emotional instability. These invisible symptoms are real, yet they’re often dismissed by others who say things like, “But you look so good!” or “Can’t you just push through for one night?”

This lack of understanding can lead to profound loneliness. When friends minimize the struggle, it’s not always out of indifference — it’s often because they don’t know how to help. Without visible signs of injury, loved ones may assume healing is complete. This disconnect can make the injured person feel guilty for needing rest or reluctant to speak up about their limits. Over time, they may withdraw not just physically, but emotionally, avoiding contact to prevent uncomfortable conversations or judgment.

Setting boundaries becomes essential, yet it’s often one of the hardest skills to develop. Many people fear being seen as difficult or ungrateful. But clear communication is not selfish — it’s necessary for recovery. Instead of saying, “I can’t come,” a more empowering approach is, “I’d love to see you, but I can only stay for 45 minutes and need a quiet spot to sit.” This gives others a chance to understand and support, rather than interpret absence as rejection.

Education also plays a role. Sharing simple information — such as how fatigue after injury is different from normal tiredness — can help loved ones empathize. Some find it helpful to use analogies, like comparing their energy to a phone battery that only charges to 60%. When others understand the limitations, they’re more likely to respect them. Building this bridge of understanding reduces isolation and strengthens relationships during a vulnerable time.

The Trap of Overcompensation

In the desire to prove they’re healing, some individuals fall into the trap of overcompensation. They accept every invitation, stay out too long, or push through pain to appear capable. This behavior often stems from fear — fear of being seen as weak, dependent, or left behind. While the intention is positive, the outcome can be harmful. Overexertion during recovery frequently leads to setbacks, a pattern known as the “boom and bust” cycle.

The boom phase feels productive: attending events, resuming routines, showing others they’re “back.” But this surge of activity exceeds the body’s current capacity. The result is a bust — increased pain, extreme fatigue, disrupted sleep, or even delayed healing. The person may then need days or weeks to recover from the outing itself, creating a frustrating loop of progress and regression.

This cycle is not a sign of failure. It’s a signal that the body’s limits are being tested. The problem isn’t socializing — it’s the timing and intensity. Measuring progress by appearances — who you can see, where you can go — is misleading. True recovery is better measured by consistency: Can you manage daily tasks without flare-ups? Do you feel more stable over time? Are you protecting rest as diligently as activity?

Breaking the boom and bust pattern requires a shift in mindset. Instead of asking, “Can I do this?” a better question is, “Should I do this right now?” This subtle change introduces self-awareness and long-term thinking. It allows space for pride in small victories — like leaving an event early without guilt — and recognizes that healing is not linear. Progress isn’t about doing more; it’s about doing what’s sustainable.

Rehabilitation Methods That Support Healthy Reintegration

Effective rehabilitation extends beyond physical therapy exercises and medical appointments. It includes strategies that support mental, emotional, and social recovery. One of the most valuable approaches is graded exposure — a gradual, step-by-step return to activities, including social ones. This method, used in both physical and psychological rehabilitation, helps the body and mind adapt without overwhelming the system.

For example, instead of jumping into a three-hour dinner with a large group, a person might start with a 30-minute coffee meet-up with one friend in a quiet café. The next week, they might extend the time to 45 minutes or invite a second person. Each step is based on tolerance, not comparison. If the first outing leaves them fatigued the next day, they know to keep the next one shorter or wait longer before increasing intensity. This builds confidence without risk.

Mindfulness techniques also play a key role in social reintegration. Practices like focused breathing, body scans, or brief meditation help individuals stay present and manage anxiety in social settings. When the mind starts to race with thoughts like “I don’t belong here” or “I’m slowing everyone down,” mindfulness offers a way to gently return to the moment. These tools don’t eliminate discomfort, but they reduce its power.

Scheduling downtime is equally important. Planning a rest period before and after a social event helps regulate energy. For instance, taking a nap before a lunch date or reserving the evening for quiet time allows the body to prepare and recover. This isn’t weakness — it’s strategy. Just as athletes plan recovery between training sessions, those healing from injury must treat rest as part of the process, not an afterthought.

Choosing the Right Environment Matters

Not all social settings are created equal when it comes to recovery. A loud concert, a packed birthday party, or a long road trip with multiple stops places high demands on the nervous system. In contrast, a daytime walk in the park, a quiet brunch with one friend, or a short phone call requires less energy and offers more control. The key is matching the environment to current capacity.

Low-demand settings share common features: they are predictable, quiet, and allow for easy exit. A person can leave a coffee shop without disrupting a group, but leaving a dinner party early may feel socially risky. Choosing places where they can sit comfortably, avoid bright lights or loud sounds, and take breaks as needed reduces anxiety and prevents overexertion.

Daytime events are often better than evening ones, as fatigue tends to accumulate throughout the day. Smaller groups are easier to manage than large gatherings, where tracking multiple conversations is mentally taxing. Virtual meet-ups, such as video calls, offer connection without the physical strain of travel or navigating public spaces. These options aren’t substitutes for “real” socializing — they are valid forms of connection that honor the healing process.

Having control over duration and exit options is empowering. Knowing you can leave after 30 minutes, or that your friend will pick you up if you’re overwhelmed, reduces pressure. This sense of safety allows for more relaxed interaction. Over time, as stamina improves, individuals can gradually explore more complex environments. But the foundation is built on smart, low-risk choices that protect progress.

Redefining Connection During Healing

True connection doesn’t depend on big events or public appearances. During recovery, the most meaningful interactions often happen in quiet moments: a heartfelt conversation on the porch, a shared cup of tea, a simple “I’m thinking of you” text. Shifting the focus from quantity to quality allows individuals to maintain relationships without overextending themselves.

One-on-one time is often more fulfilling than group settings. It requires less energy, allows for deeper conversation, and reduces sensory load. Virtual check-ins can be just as valuable, especially when physical presence isn’t possible. Sending a voice message, sharing a photo, or watching a movie together online keeps bonds strong without strain.

Quiet activities — reading together, gardening, listening to music — offer connection without pressure to perform. These moments don’t require constant talking or social performance. They allow presence without exhaustion. Recognizing that healing doesn’t have to be lonely, but it may look different, helps reduce feelings of loss.

Healing is not just about returning to who you were — it’s about becoming who you are now. This journey includes redefining what social life means, honoring limits, and practicing self-compassion. Progress isn’t measured by how many events you attend, but by how well you care for yourself in the process. When recovery is approached with patience and intention, the result is not just physical healing, but a deeper, more resilient sense of self. The body heals with time, but the spirit heals with kindness — to oneself and from others who learn to walk beside, not ahead.