Why Exercise Feels Impossible When You’re Depressed — And What Actually Helps

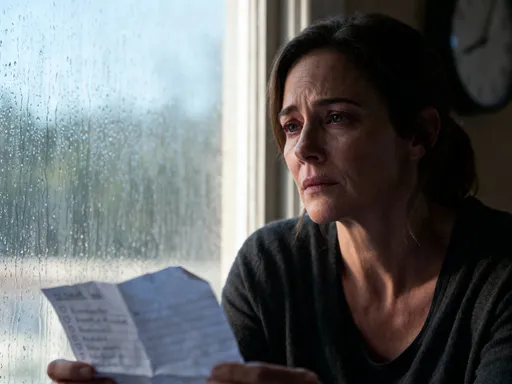

Depression doesn’t just weigh on your mind—it drags your body down too. Many people know exercise can help, but when you’re struggling to get out of bed, the idea of a workout feels like a joke. I’ve been there. The real issue isn’t laziness—it’s misunderstanding how depression reshapes your energy, motivation, and sense of self. This isn’t about quick fixes, but about navigating the real obstacles with patience and practical steps. For countless women managing household responsibilities, personal well-being often takes a backseat, especially when emotional exhaustion blurs the line between fatigue and failure. Recognizing that movement is not a measure of worth—but a tool for reconnection—can transform how we approach healing. This article explores why physical activity feels so unreachable during low periods and offers science-backed, compassionate strategies to make it possible again.

The Hidden Battle: Why “Just Move” Doesn’t Work

When someone says, “You should try exercising—it helps with depression,” the intention is kind. But for those living with depression, this advice can feel dismissive, even hurtful. The expectation to “just move” overlooks a fundamental truth: depression alters the brain’s chemistry in ways that directly affect physical energy and motivation. It’s not a lack of willpower or discipline; it’s a neurological shift. Research shows that depression impacts the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for decision-making and goal-directed behavior, making even simple tasks feel overwhelming. Dopamine, the neurotransmitter linked to motivation and reward, is often dysregulated, which means the brain doesn’t register pleasure or incentive in the same way. As a result, the thought of lacing up sneakers or stepping onto a yoga mat doesn’t spark inspiration—it triggers resistance.

Additionally, depression frequently causes profound physical fatigue. It’s not the kind of tiredness that sleep fixes. It’s a deep, bone-level exhaustion that makes lifting an arm feel like climbing a mountain. This fatigue isn’t imagined—it’s measurable. Studies using objective markers like heart rate variability and cortisol levels confirm that depression activates the body’s stress systems chronically, leaving little reserve for voluntary effort. When someone is in this state, being told to exercise can feel like being asked to run a marathon with no training, no water, and no finish line in sight. The gap between knowing what might help and being able to act on it becomes a canyon.

Another layer of misunderstanding lies in the stigma around inactivity. Society often equates rest with laziness, especially for women who are expected to manage homes, children, and emotional labor without pause. When depression silences that inner drive, the self-criticism can be crushing. “Why can’t I just do the dishes?” “Why am I lying here when there’s so much to do?” These thoughts spiral, reinforcing feelings of failure. But inactivity during depression is not a moral failing—it’s a symptom. Recognizing this distinction is the first step toward self-compassion and realistic change. Movement must be redefined not as a test of strength, but as a gentle invitation to reconnect with the body, on its own terms.

Missteps That Backfire: Common Exercise Pitfalls in Depression

Even with the best intentions, many attempts to use exercise as a tool for managing depression fail—not because movement doesn’t help, but because the approach is mismatched to emotional reality. One of the most common missteps is setting goals that are too ambitious too soon. A woman might watch a wellness video and decide to start with a 30-minute high-intensity interval training (HIIT) session, only to collapse on the couch afterward, feeling worse than before. The physical strain can amplify mental fatigue, and the emotional toll of “failing” to complete the workout deepens the sense of inadequacy. This isn’t a lack of commitment—it’s a mismatch between intention and capacity.

Another frequent error is choosing the wrong type of activity for the current emotional state. High-intensity workouts, while beneficial for some, can feel punishing when the nervous system is already overwhelmed. For someone in a depressive episode, the adrenaline surge from intense exercise may increase anxiety or lead to emotional shutdown. The body may interpret the exertion as stress, triggering a fight-or-flight response instead of the intended calming effect. This is especially true when exercise is framed as a form of self-improvement or punishment for perceived shortcomings. “I need to work off that cake I ate yesterday” or “I have to earn the right to rest” are thoughts that turn movement into another source of pressure, not relief.

Well-meaning advice from friends or online sources often misses this nuance. Phrases like “Just push through it” or “No pain, no gain” are not only unhelpful—they can be harmful. They ignore the fact that depression already creates internal pain. Adding physical strain without emotional support rarely leads to sustainable change. Instead, it reinforces the belief that effort should be rewarded immediately, and when it isn’t, the person feels broken. This cycle of attempt, burnout, guilt, and withdrawal becomes a barrier to future attempts. The solution isn’t to try harder, but to try differently—starting smaller, moving slower, and honoring the body’s signals without judgment.

Rethinking Movement: From Workout to Gentle Reconnection

To make movement accessible during depression, we must redefine what it means to “exercise.” It’s time to shift from a performance-based mindset—measured in reps, miles, or minutes—to a self-care mindset focused on presence and permission. Movement doesn’t have to mean sweating, panting, or achieving a certain heart rate. It can mean sitting up slowly, reaching your arms toward the ceiling, or taking three deep breaths while standing at the kitchen sink. These micro-movements are not trivial; they are acts of re-engagement with the body.

Think of it like relearning how to walk after an injury. You wouldn’t start with a sprint. You’d begin with small steps, supported and intentional. The same principle applies here. Gentle movement helps rebuild a sense of agency—the feeling that you can influence your own experience, even slightly. When depression makes you feel powerless, the ability to choose to stand up, stretch, or step outside becomes meaningful. It’s not about intensity; it’s about intention. Each small action sends a message to the brain: “I am still here. I can still act.” Over time, these moments accumulate, creating a foundation for greater stability.

Practices like mindful stretching, seated yoga, or slow walking can be especially effective. They combine physical motion with breath awareness, which helps regulate the nervous system. Rhythmic, repetitive movements—like rocking in a chair or swaying side to side—can have a calming effect similar to how a parent soothes a child. These actions don’t require energy reserves; they generate them. The goal isn’t to exhaust the body to feel better later, but to use movement as a way to feel slightly more present now. When we stop measuring progress by external standards and start honoring internal cues, movement becomes less of a demand and more of a dialogue with ourselves.

Finding Your Entry Point: Matching Activity to Energy Levels

One of the most practical ways to begin is by aligning movement with your current energy level. Instead of a one-size-fits-all routine, think of movement as a ladder with different rungs—each matching a different capacity. On days when getting out of bed feels impossible, the goal isn’t a walk around the block. It’s something much smaller: rolling to the edge of the bed, sitting up, or placing your feet on the floor. These are valid forms of movement. They require minimal effort but carry symbolic weight. They are proof that action is still possible, even in small doses.

For those with slightly more energy, room-based activities can help. Try sitting in a chair and lifting your arms slowly, five times. Or stand and shift your weight from one foot to the other, noticing the sensation in your legs. You might sway gently or rotate your shoulders. These actions don’t require special clothes or equipment. They can be done in pajamas, without leaving the room. The key is consistency, not duration. Even 60 seconds of intentional movement can shift your state slightly—like turning on a dimmer switch instead of waiting for the full light.

When energy allows, house-based movement becomes an option. Walking from the bedroom to the kitchen. Standing at the window and watching the sky for two minutes. Hanging up laundry or watering a plant. These everyday actions count. They connect you to your environment and break the cycle of stagnation. And when you’re ready for the outdoors, start with the threshold: open the door, step outside, feel the air. You don’t have to walk far. Standing on the porch for one minute is enough. The goal isn’t distance—it’s reconnection. By matching activity to energy, you remove the pressure to perform and create space for realistic, sustainable progress.

The Role of Routine: Building Predictability Without Pressure

Depression often distorts time and disrupts routine. Days blur together. Mornings feel indistinguishable from nights. This lack of structure can deepen feelings of disorientation and helplessness. Introducing a small, predictable movement practice can help restore a sense of order. The key is to keep it simple and repeatable—something you can do most days, even when motivation is low. For example, five minutes of seated stretching every morning after waking. Or three deep breaths before standing up from the couch. These tiny rituals become anchors in an otherwise drifting day.

Neuroscience supports this approach. The brain thrives on patterns, especially during times of emotional distress. When we repeat a small action regularly, it strengthens neural pathways associated with habit and self-efficacy. Over time, the behavior becomes automatic, requiring less mental effort. This is crucial when depression depletes cognitive resources. You don’t have to decide each day whether to do it—you just do it, like brushing your teeth. And because the action is small, the risk of failure is low, which protects self-esteem.

It’s important to design routines that don’t rely on motivation. Motivation fluctuates; habits persist. A successful routine is one that feels doable even on bad days. If you miss a day, there’s no need for self-criticism. Simply return to it the next day. The goal isn’t perfection—it’s continuity. Over weeks and months, these small practices build a quiet confidence: “I showed up for myself, again.” That consistency, not intensity, becomes the foundation for deeper healing.

Beyond the Body: How Movement Supports Emotional Regulation

While many believe exercise helps depression solely by releasing endorphins—the so-called “feel-good” chemicals—this explanation is oversimplified and often misleading. The emotional benefits of movement are more nuanced and vary from person to person. For some, the rhythm of walking can create a meditative state, quieting the mind’s chatter. For others, feeling the sun on their skin or the wind in their hair provides a grounding sensory experience that pulls them out of rumination. These moments of presence, however brief, disrupt the cycle of negative thoughts.

Movement also influences the autonomic nervous system. Slow, rhythmic activities like walking, tai chi, or gentle stretching activate the parasympathetic system—the “rest and digest” mode. This helps lower heart rate, reduce muscle tension, and calm the breath. When the body feels safer, the mind follows. This isn’t about instant relief; it’s about gradual regulation. Over time, regular gentle movement can improve sleep quality, which in turn supports mood stability. Poor sleep worsens depression, and better sleep creates a positive feedback loop.

Additionally, movement can restore a sense of control. Depression often makes life feel unpredictable and chaotic. Choosing to move—even slightly—introduces an element of agency. “I decided to stand. I chose to step outside.” These small decisions rebuild the belief that your actions matter. And when you begin to trust that you can influence your experience, even in tiny ways, hope becomes possible again. The emotional benefits aren’t dramatic; they’re subtle, like the first light of dawn after a long night. But they are real, and they accumulate.

Staying on Track: Self-Compassion Over Accountability

One of the greatest obstacles to sustained movement during depression is self-criticism. Many women internalize cultural messages that equate productivity with worth. When they can’t maintain a routine, they blame themselves: “I’m weak. I failed again.” But this harsh inner voice only deepens the wound. A more effective approach is self-compassion—the practice of treating yourself with the same kindness you’d offer a friend. When you miss a day, instead of scolding yourself, try saying, “I’m doing my best. Today was hard. I’ll try again tomorrow.”

Self-compassion isn’t about making excuses—it’s about reducing shame. Research shows that people who practice self-compassion are more likely to persist in healthy behaviors because they don’t fear failure. They understand that setbacks are part of the process, not proof of inadequacy. Celebrating micro-wins—like standing up without rushing, or taking three deep breaths—reinforces progress in a way that tracking apps or fitness goals cannot. It’s not about how far you went, but that you showed up at all.

It’s also important to know when to seek professional support. Movement is a helpful tool, but it’s not a substitute for therapy, medication, or medical care. If depression is severe, persistent, or interfering with daily functioning, a healthcare provider should be consulted. A doctor or mental health professional can help create a comprehensive plan that includes appropriate treatment. Movement can be part of that plan, but it should never be the only strategy. Healing is not a solo journey, and asking for help is a sign of strength, not weakness.

True progress in depression recovery isn’t measured in miles run or calories burned, but in moments of choice—choosing to stand, to step outside, to move gently toward yourself. Exercise guidance shouldn’t add pressure; it should offer a bridge back to agency, one breath, one step at a time. With patience and realistic expectations, movement can become not a demand, but a quiet act of care. It’s not about fixing yourself—it’s about remembering that you are worth the effort, exactly as you are.